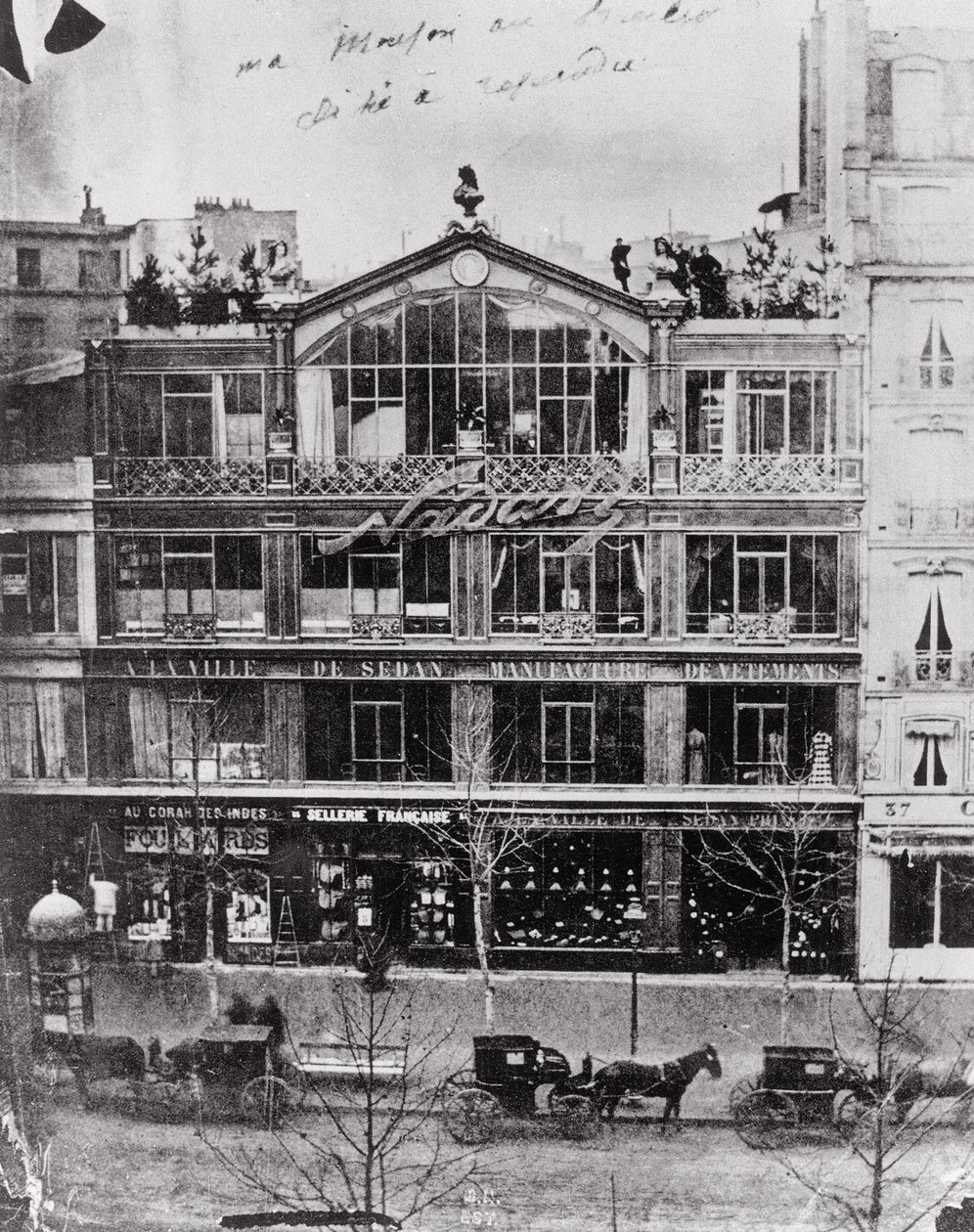

Nadar, Studio of Nadar at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, c. 1855, photograph

April 15, 1874. In the recently vacated gallery space of the French photographer Nadar at 35 boulevard des Capucines, 30 artists hung 165 artworks on the gallery’s walls. A rough brownish-red linen, left there by Nadar, filled the space. Artists hung draperies around the artworks, mimicking the en vogue style favored in private galleries of the time. The viewing hours were set fashionably late. This new exhibition, organized by the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs, & etc., or the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, etc., was the first Impressionist exhibition.

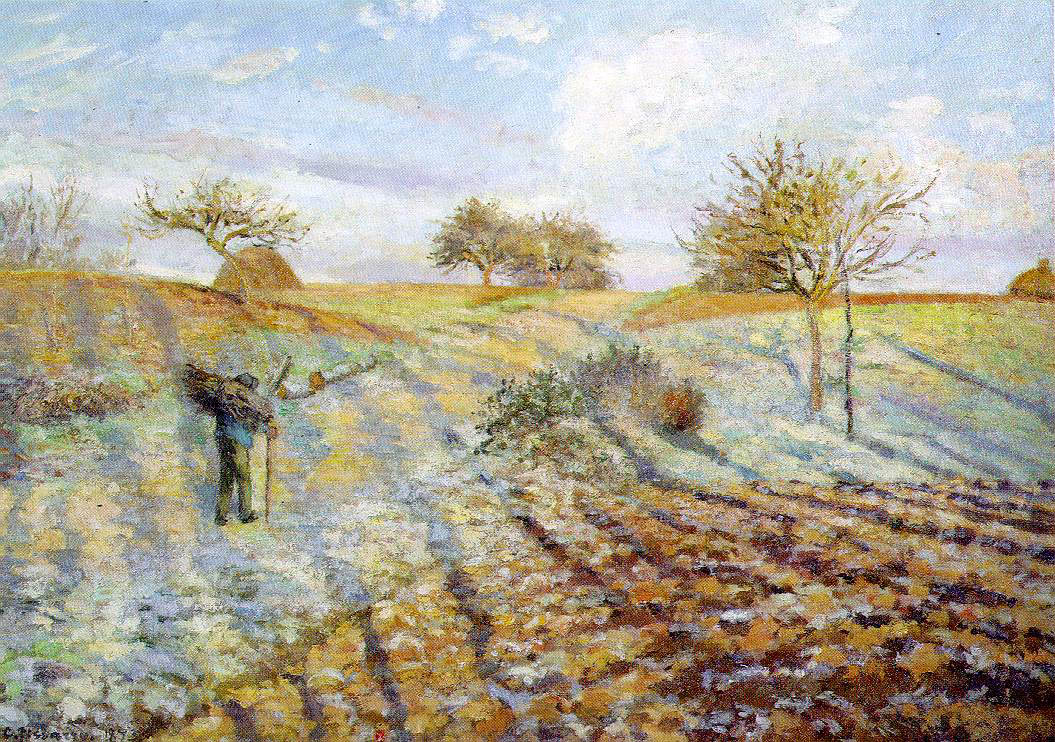

The first exhibition, beloved now, was not favorably received. In the satirical magazine Le Charivari, French art critic Louis Leroy imagined a conversation between two visitors to Nadar’s studio. In front of Camille Pissarro’s landscape Hoarfrost, the “good man thought that the lenses of his spectacles were dirty. He wiped them carefully and replaced them on his nose.” Entreating his guest, the narrator reminds him, “You see… a hoarfrost on deeply ploughed furrows,” to which the consternated guest replies, “Those furrows? That frost? But they are palette-scraping placed uniformly on a dirty canvas. It has neither head nor tail, top nor bottom, front nor back.” If it was an impression, as the narrator suggests, it was “a funny impression!”

Camille Pissarro, Hoarfrost, 1873, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay

This funny impression, and this type of landscape, became respected as one of the most pivotal art movements of the nineteenth century and as one of the most ‘true to nature’ styles in which to paint. The direct observation of nature often recorded ‘in the field’ or en plein air reverberated through time and geography, and deeply affects the approach to wildlife art to this day.

Within the Woodson’s collection, Impressionism looms large. Whether it’s the work of Théodore Rousseau, a French Barbizon school painter whose work anticipated the Impressionists, Gustave Caillebotte, one of the first patrons of the Impressionists, Childe Hassam, who took the new movement and translated it to an American context, or Mary Cassatt who delicately etched the bourgeoise interior of a woman with her parrot, the effects of April 15, 1874 — now nearing its 150th anniversary — can be felt here in Wausau, April 10, 2024.

Théodore Rousseau, Sunset, 1850-60, oil on cradled panel, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Nancy Woodson Spire Foundation