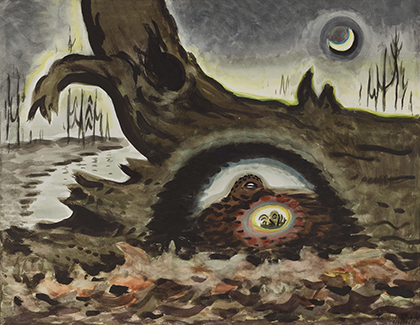

Recently acquired by the Woodson Art Museum, American artist Charles Burchfield’s large-scale watercolor, Brooding Bird, radiates the power of nature: calligraphic strokes describe vibrating, leafless trees at the horizon line. The crescent moon exudes slivers of color against the dark circle of the night sky. A log, hollowed out at its center, gleams with yellow-green lines emanating from its bark. A scattering of brown leaves nearly sparks to life set aglow by nestling red among the brown.

Charles Burchfield, Brooding Bird, 1963 (1919), watercolor on paper laid down on paperboard

Within the tree’s hollow, two birds rest. The first appears almost tree-like itself with its dark brown and textured plumage. It turns its head inward, eye held in a peaceful slit. Within or perhaps under the brown bird, a second bird sits. It is contained within luminous, concentric circles of color – red, blue, and yellow – that echo the colors of the crescent moon. Its features are unformed, and we see only its head. This is either a bird about to be or being born – the ultimate expression of nature’s power in the act of birth.

Yet, brooding takes on both its meanings here. It is both the bird’s behavior of sitting on a clutch of eggs to incubate them and the sense of the darkly somber. Burchfield painted Brooding Bird in 1919 after he had returned from fighting in World War I. While there, he was assigned to the camouflage unit in the Army. He used his artistic talents to disguise tanks and create artificial hills. Suddenly, the wooden, downy colors of the brown bird take on a different tone. The bird becomes part of the tree; her downy colors camouflage the new mother from nature’s implied threat. Indeed, after Burchfield’s return from the war, his work took on a tenser, more somber mood. He often depicted coal mines, small towns, and life from the perspective of birds.

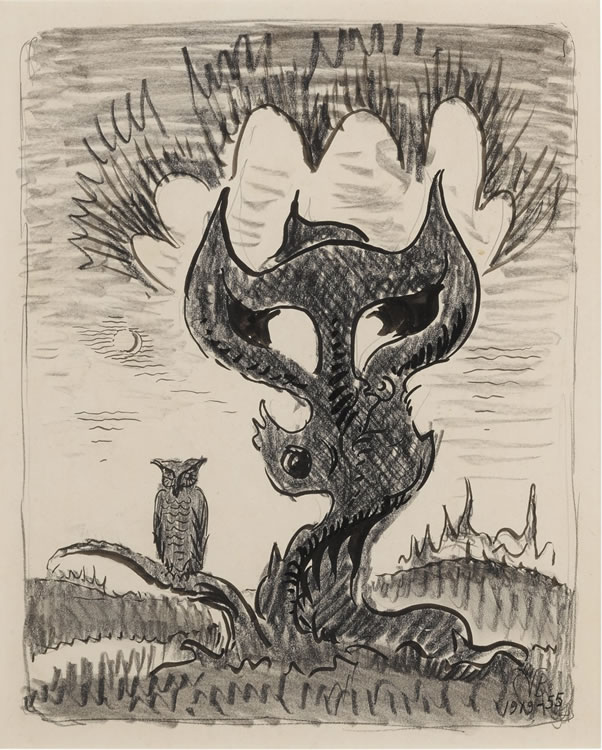

Charles Burchfield, The Tree of the Owl, 1955 (1919), ink, charcoal and pencil on paper laid down on paperboard

Another 1919 Burchfield artwork, in a private collection, has striking similarities. The Tree of the Owl shows an owl perched on a low branch among swampy ground. A tree radiates from the drawing’s center. It emits an auratic glow. Burchfield seems to make the tree itself a bird; the knotted roiling center looks like an upside-down bird, with its large black eye gazing out at us. At right, a smaller outline of a bird shape seems to hover. The birds from Brooding Bird are turned upside down, now fully merged with the tree that housed them.

The somber tone in both 1919 images contributes to one of the most interesting elements of Brooding Bird – its date demarcation. Burchfield’s painting in 1919 was markedly different from his work of the pre-war period, and his New York dealer, Mary Mowbray-Clarke, argued that the new, melancholy tone would dissuade collectors. Burchfield made the difficult choice to destroy his artworks of the period – an action he would come to regret in later years.

Following a 1955 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, he was encouraged to return to his 1919 works, writing in his journal: “Beginning on Jan. 3 (Monday) Bertha and I have attacked the problems of making scrapbooks of my notes & studies for pictures.” This return to the past prompted the artist to re-create his destroyed 1919 artworks in the 1950s and 1960s. This recommitment to his earlier work resulted in Brooding Bird’s “reconstruction” in 1963, four years before the artist’s death.

See Brooding Bird, on view at the Woodson in April.